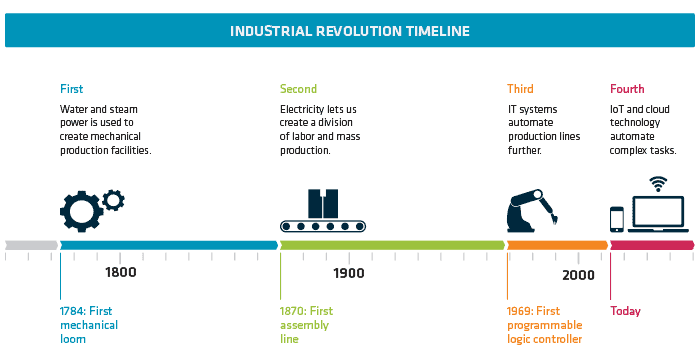

The Fourth Industrial Revolution (Part 3) Industry 4.0, Digital Transformation

In this third entry in the series; we cover the attributes of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, why it’s important, and the implications for business.

In Klaus Schwab’s book “The Fourth Industrial Revolution” Schwab coins the title phrase in his book. Others use terms such as “Industry 4.0” (BMBF-Internetredaktion, n.d.) and the “Digital Transformation” (“Digital Transformation Initiative,” n.d.). All three terms in general, refer to the application of an accelerating set of technologies, and the resulting impact on society, business, and industry.

Great, so what?

Well, first let’s identify the technology megatrends Schwab describes as part of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR). “All new developments,” Schwab asserts, “have a single key feature in common; the pervasive power of digitization and information technology.” (Schwab, 2016). Schwab organizes the trends into three broad categories, physical, digital, and biological.

Physical

The physical technologies that Schwab refers to in 4IR are autonomous vehicles, 3D printing, advanced robotics, and new materials.

Autonomous Vehicles

I attended CES 2018 this past January, and if there was a theme of the show; autonomous vehicles, 3D printing, advanced robotics, and emerging AI would have been the subtitle.

Conceptually the autonomous vehicle contains technology facilitating operation of a variety of vehicles with minimal or no human intervention. The driverless car has been in the technology vernacular since at least 1926 (“Phantom Auto Will Tour City,” 1926), however, the vehicles at CES were far removed from the radio controlled experiments in the first half of the 20th century.

Robby – Local Individual Delivery

The SAE defines six levels of automated driving, ranging from level 0 – manual, in what we know today as a contemporary car, to level 5 – fully automated with a human passenger acting in the sole capacity of management (“SAE international standard J3016.,” 2014).

While we will get to artificial intelligence in another post; AI is particularly relevant to autonomous vehicles. In 2016 an experimental vehicle was tested on the roads of Monmouth County, New Jersey. Unlike the experimental vehicles designed by any number of other research groups from GM to Tesla, this vehicle, developed by Nvidia (yes, the same Nvidia that manufactures graphics cards for the PC and set-top consoles where your children are playing Far Cry), wasn’t operating from one instruction provided by programmer or engineer. This car taught itself to drive through a combination of human driver observation, and self-adapting machine learning algorithms. The fundamental challenge is that the engineers that design these systems aren’t completely clear how the car makes its decisions. Joel Dudley, PhD, Executive Vice President of Precision Health at Mount Sinai, and Chief Scientist of the hospital’s AI intiative called “Deep Patient,” states “We can build these models, but we don’t know how they work” (Knight, 2017).

Toyota Lexus Autonomous LS350

The implications for business are fairly clear, we’re not talking about just automobiles, similar algorithms are being considered by Airbus and Boeing for use in flight control systems. And levels of autonomy exist in everything from military and commercial drones, trucks and boats. In fact, these technologies will have profound effects on logistics and supply chains (Schwab, 2016). Additionally, being cybernetic systems, they are targets of attack and vulnerable.

Key Message and Takeaway:

Everything from consumer automotive, public transportation, supply chain, logistics, consumer deliveries will be affected by autonomous vehicles; and much sooner than you think, 5-7 years not decades. Is your supply chain ready for the changes? Autonomous Uber anyone?

3D Printing

I remember when I saw the first prototyping stereolithography system when I worked for Mark IV Luminator in the mid-1990s. It used ultraviolet light to cure layer by layer of a model out of a vat of resin (looking very much like a vat of goo from a 1960’s sci-fi movie). The build volume of the printer was 250 cubic mm, each part produced came at a cost of $100 to $500. The machine itself was about the size of 2 4-drawer filing cabinets and came at a cost of about $200,000 dollars (“Wohlers Associates,” n.d.).

Earlier this summer, I went to MicroCenter and purchased a wireless 200 cubic mm FDM (full deposition modeling) printer for just under $400. This printer uses a standard 1.75mm reel filament that comes in a number of materials, everything from PLA and ABS plastics, to carbon fiber and wood. 1Kg reel of filament runs anywhere from $30 – $50.

Again, so what?

Additive manufacturing allows for the production of not just fragile prototype parts, the kind I first saw in the 1990s. Today’s additive manufacturing lends itself to the manufacturing of replacement part, prototypes, and objects produced from unique

Ever lost or broke those stupid clips on your shelving? Print new ones, and yes, this is an actual clip from a cabinet.

materials that would have been cost prohibitive only a few years ago.

For me, I decided to purchase a 3D printer for a couple of purposes; first I am a bass guitar builder, and I use the printer to produce prototype control knobs for my guitar builds, and now there are very replacement few parts I need around the house that can’t be replaced with 3D printed part (see below).

Now DMLS (direct metal laser sintering) printers that can produce production quality metal alloy parts that can be used in everything from biomedical to aerospace (Stratsys, 2018).

Key Message and Takeaway:

3D printing is not only here, but it is also becoming affordable for consumers (though still primarily in the maker community) and in broad scale manufacturing. No longer will repair depots need to carry an inventory of replacement parts; need a replacement knob for a broken one on the

- Guitar control knob prototypes from my 3D printer

- Guitar control knob prototypes from my 3D printer

kitchen range, the local hardware store was out of 90-degree elbows, need a replacement narrow tip for your vacuum (Thingiverse, 2018)? Download the part and print it on the 3D printer next to the multifunction printer in the office. Seriously, these are all parts available right now and can be printed.

We will continue to unpack each of the technologies and give you a few things to look out for as these technologies mature and become mainstream. In the next post, we will continue with the physical impact of 4IR with a discussion on advanced robotics and new materials.

References:

BMBF-Internetredaktion. (n.d.). Industrie 4.0 – BMBF. Retrieved December 11, 2018, from https://www.bmbf.de/de/zukunftsprojekt-industrie-4-0-848.html

Digital Transformation Initiative. (n.d.). Retrieved December 11, 2018, from http://wef.ch/2hU0x7I

Knight, W. (2017). The Dark Secret of at the heart of AI. Retrieved December 12, 2018, from https://www.technologyreview.com/s/604087/the-dark-secret-at-the-heart-of-ai/

Phantom Auto Will Tour City. (1926, December 8). Millwaukee Sentinel. Retrieved from https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=unBQAAAAIBAJ&sjid=QQ8EAAAAIBAJ&pg=7304%2C3766749

SAE international standard J3016. (2014, January). SAE.

Schwab, K. (2016). The Fourth Industrial Revolution. World Economic Forum.

Stratsys. (2018). DMLS 3D Print Usage. Retrieved December 12, 2018, from https://www.stratasysdirect.com/technologies/direct-metal-laser-sintering

Thingiverse. (2018). Household Replacements. Retrieved December 12, 2018, from https://www.thingiverse.com/explore/newest/household/replacement-parts/page:3

Wohlers Associates. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2018, from https://wohlersassociates.com/mr.html